Together with many others, we have come to see male supremacy as a system causing a great deal of violence and harm not only in the world at large, but also within our own radical and Left movements. Whether it’s physical or sexual abuse, talking over others, unsolicited neediness, or shrugging off emotional and logistical work, practices of male supremacy often work to undermine solidarity and community. They harm, traumatize and push people away, placing even more obstacles in our collective path to social transformation.

Male supremacist behavior within our organizing spaces is often allowed to go unchecked because the struggle is thought to be elsewhere, whether in the streets or the halls of government. In addition, some of the most obvious forms of this behavior, such as male sexual violence, can feel especially difficult to address for those of us who recognize that the police and prisons not only fail to prevent this violence but actually produce and reproduce systems of heteropatriarchy, white supremacy and capitalism. Left unaddressed, however, male violence within our communities reinforces the status quo and undermines the belief that a better world is within our collective capacity to create. The joint statement issued back in 2001 as a collaboration by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence and Critical Resistance on ‘Gender Violence and the Prison Industrial Complex’ is particularly instructive on this point, urging “all men in social justice movements to take particular responsibility to address and organize around gender violence in their communities as a primary strategy for addressing violence and colonialism. We challenge men to address how their own histories of victimization have hindered their ability to establish gender justice in their communities.”

Through facilitating or supporting various accountability processes, we’ve also learned that men who have caused harm are often easier to reach if they are engaged by people they already trust, and are frequently more likely to be accountable if they can maintain pre-existing relationships or even build new ones. When we address the problem through this lens, it becomes clear that the responses often employed to address male violence—public shaming, physical punishment, exile from spaces or a community, calling the police or just doing nothing—are at best insufficient and at worst actually counterproductive. Demonization, isolation, retaliatory violence and/or state intervention not only lead to partial or ineffective solutions, but ultimately can be destructive for all those scapegoated and targeted by the prison industrial complex.

Study-into-Action

The question becomes: how do we create responses to these widespread harms that have the potential to actually build solidarity, create community, and support the healing of those who have been harmed while also challenging the male supremacist context within which the incident occurred? How do we do this without relying on unnecessary violence, exclusion, or state systems? We might call responses that meet these criteria transformative justice, at least to the degree that they seek to not only address the harm but also to transform the convictions and structural conditions that facilitated the harm happening in the first place.

When the three of us first got together, we spent months discussing what we wanted to see and help to create in terms of community responses to violence. The “Transformative Justice Collaborative” model initiated by Generation Five, a Bay Area-based organization focused on ending child sexual abuse, was particularly inspiring to us. All three of us had been involved with work organizing around gender violence or child sexual abuse, and one of us had just co-facilitated a circle process to hold accountable a prominent local activist who had sexually assaulted within the citywide student movement. When we examined the landscape of organizations and collectives developing community-based responses to harm, they were made up predominantly, if not entirely, of cisgender women, transgender and gender non-conforming organizers and activists. We felt that we needed more cisgender men engaged in this work and that we would all need to do some advanced work specifically around male privilege and violence in order to enter future organizing work with more shared analysis, capacity and commitment. In the fall of 2008, we founded the Challenging Male Supremacy Project. We made a conscious decision to use the still somewhat unfamiliar term ‘cisgender’ in doing this work, a term coined by transgender activists used to describe those of us who identify with the sex we were assigned at birth and the gender identity we were raised with.

In an attempt to bring more cis men into this work, as well as to meet an expressed need to challenge male supremacy within various NYC social justice organizing communities, we facilitated our first Study-into-Action from May 2009 to January 2010. For nine months, this group discussed, read and reflected on male supremacy both in our personal as well as our political lives. Facilitating this process for a diverse group of cisgender men from all over the city, we tried to construct spaces and practices of confronting male supremacy in its concrete manifestations, as it intersects with other systems of oppression. For example, in one session we broke into groups to analyze how different racialized masculinities are represented in mainstream media, be it Black, Caribbean, Latino, Asian or white. This was instructive for exploring both how we had related to our own particularly racialized masculinities growing up and how we have been targeted, privileged, or otherwise pigeon-holed in the popular imagination. One of the questions that remained at the end of this session was whether we were seeking to construct new and better masculinities or move beyond and end masculinity.

One novel element of our monthly sessions was our practice of Somatics, an integrative approach to healing and transformation that understands and treats human beings as a complex of mind, body and spirit. With support from Generation Five co-founder and long-time Somatics instructor Staci Haines, who co-facilitated our first session, we tried to adapt Somatics to addressing shared privilege and power (from its more common application to healing from experiences of trauma). We communicated to the group that we incorporated Somatics not simply as a practice of self-help or self-improvement—which is often socially decontextualized and strongly individualistic—but because we feel strongly that we cannot just think and talk our way out of male privilege and male violence. This felt particularly important to us as so much of this violence manifests in relationship to bodies and what we do with and to them. As we shared in the group, we need to work with our whole organisms and transform ourselves at the level of everyday behaviors in order to shift our practices of male privilege.

Building Practice

It became clear over this first cycle of work that there were recurring dynamics that we needed to address and particular skill sets that we needed to development. One key area involves the development of emotional intelligence and the capacity to provide and seek appropriate support—struggling to replace the norm of cis men who are unable to notice their own or others' emotions and emotional triggers, with one where they reciprocate the support they get and provide support for others in ways that challenge patriarchal social relations.

Another area of focus is developing a profound grasp and consistent practice of consent and moving from a legalistic framework of soliciting permission to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of power. We’ve tried to reframe consent—and particularly the word ‘no’—as something that can make healthier relations possible for all parties, and allow us to maintain connection in the future. At the same time, we’ve strived to question our basic assumptions about sexuality and desire itself, denaturalizing our sexual desires and examining the ways that they’ve been historically and culturally shaped or produced. The third area, finally, is learning to share work that has historically been relegated to women, especially in the home or in formal political settings.

Thus far, we’ve sought to work in these areas through education, skills-building and mobilization with other cis men, and in collaboration with feminist, queer and trans organizers. Part of what the latter has looked like thus far is building solidarity in analysis and practice together. In founding the CMS Project, we’ve joined a patchwork landscape of organizations and collectives in NYC working to eliminate violence against female/queer/trans individuals and communities and/or build alternative forms of safety and accountability beyond the prison industrial complex. We’ve learned from and collaborated with Support New York, a collective who have been doing work around survivor support and community accountability for several years; we’ve also been in touch with members of Reflect, Connect, Move around our shared work on gender violence, while CONNECT—an organization focused on family and gender violence—has shared space and resources with us. We continue to be inspired by Critical Resistance NYC and the People’s Justice Coalition, who are building community-based responses to state violence: the former (as part of a coalition) recently won a campaign to stop construction of a new jail in the Bronx, while the latter is working to foster and support a citywide culture of observing the police as a tactic to deter abuse and brutality on their part.

Before beginning our Study-Into-Action, we also decided to approach some of the groups doing this work and formally partner with them in organizing this project. In the role of Accountability and Support Partners, these organizations gave us feedback on a curriculum outline several months before our first session, helped to shape its structure and content, and met with us halfway through the nine-month program to again give us feedback. The groups included the Safe OUTside the System Collective of the Audre Lorde Project, Sisterfire NYC (a collective affiliated with INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence), Third Root Community Health Center, the Welfare Warriors Project of Queers for Economic Justice, and individual members of the Rock Dove Collective and an emerging queer people-of-color anti-violence group.

As the name suggests, we were hoping to culminate the Study-into-Action with some sort of collective action in support of and useful to one or more of our partners. Lacking a clear opportunity to do so, we instead organized a report back event in March, to which we each invited friends, family and members of our communities. The goals of the event were to organize something collectively between the three of us who facilitated the nine-month program and the nine participants who completed it, to broaden the dialogue and share our commitments with a larger group of people to whom we are actually accountable to in different ways and to create a platform for this dialogue to happen within the context of our accountability and support partner organizations, who also participated in the event, as a way to continue building connection and collaboration. The need for this kind of work was reflected in the packed room of around 100 people who showed up for the report back, representing a rich cross section of the city.

Next Steps

We currently find ourselves in a moment where we are attempting to hold and synthesize all the learning and feedback gained from these experiences with accountability processes, the Study-into-Action and the collective event. Our relationship with Generation Five, with whom we are deepening our understanding of transformative justice and training in Somatics, will continue to be crucial in supporting our next steps following this assessment process.

Presently, we are producing the curriculum developed for the Study-into-Action in order to share it with people from across the country this June in Detroit at the Allied Media Conference and US Social Forum. While in Detroit, we are also looking forward to collaborating with the Story Telling and Organizing Project, an organization that provides a forum and a model for “collecting and sharing stories about everyday people taking action to end interpersonal violence,” and who’s audio stories we used to help ground our discussion on accountability in one of our Study-Into-Action sessions.

Most importantly, we are looking for ways to deepen collaboration with our Accountability and Support Partners locally while continuing to engage and support the Study-into-Action participants and their communities. Whether we remain in our current formation or shift into something else will depend greatly on these two groups’ needs and desires.

In taking on this project, we have learned to embrace the fact that there are real and significant things we stand to lose by undermining male privilege, but that we have honest emotions, healthier relationships, greater dignity and a fuller humanity to gain. Through this work toward transformative justice, it is our hope that we are creating responses to violence and harm that make our vision for a better world—one that offers safety without depending on prisons—not only more likely, but also more credible.

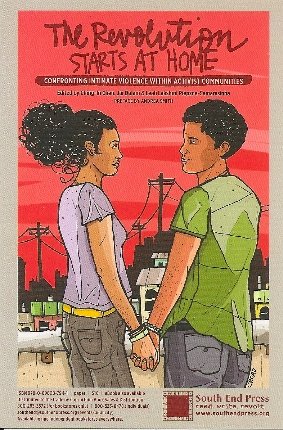

RJ Maccani, Gaurav Jashnani and Alan Greig are founders of the Challenging Male Supremacy Project. You can contact them at cmsprojectnyc [at] gmail.com. A more in-depth exploration of these themes can be found in their contribution to the forthcoming book from South End Press, “The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence in Activist Communities,” edited by Ching-In Chen, Dulani, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha.

First published in Left Turn Magazine, Issue #37 ("From Detroit to Dakar"), June/July 2010. Reprinted with permission.