Dr Jane Meyrick summarises part of her new sexual violence ‘explainer’ book #MeToo for Women and Men (click through blue highlighted hyperlinks to access source documents)

“All too often I hear or read men saying ‘Not all men are like that’…but these men need to play a more active role in preventing harassment by actively challenging the men who do behave in such a manner’ (Member of the public, 2018)

Calling in not calling out

All the evidence around how to work with men and boys around gender-based violence starts with the need to appeal to men rather than demonizing them, acknowledging that there are a range of men as there are a range of women. Men and boys need to be able to call in their friends in a supportive way to address harassing behaviour and get them to recognise the impact. Often the difficulty with ‘being a real man’ is other men and how groups of men ‘perform’ their masculinity for their mates. Compassionate allies are at the heart of understanding and interrupting men who do. Where those voices come from is important, men are more influenced by other men’s willingness to intervene.

Sexual violence is an expression of one route to masculinity and is a problem for all of us.

“I think men need to talk to each other and say actually, dude, don’t do that, that’s really messed up.” (Purple Drum, 2016)

Why

Men’s motives in engaging on the issue may well not be inequality or feminism, but with #Metoo, a recognition that this has and is happening to many women they know and love.

“Over the past few months, I have been horrified by non-stop revelations about sex abuse by men. It’s not just the grim details — it’s the underlying truth that each new story drives home: that this is normal, and especially normal wherever men have power”(David Reed)

For those on the up side of male dominance, doing something rather than nothing needs a motive such as pointing to the gains of gender equality as positive for all.

Let us make no mistake, the evidence is clear that these norms are just as harmful to the men trying to stick to them as the women and girls on the receiving end. We see greater violence directed both outwards, at others or inwards in mental health struggles and suicide. Aging out of the roles available for ‘real men’ can see men’s self-worth erased as they are less able to be the ‘action hero’ but also as they feel they cannot ask for help with their mental or ill health. Author of Trainspotting, Irving Welsh sums it up

“the patriarchy’s been fucking shit for men, too – they’ve been fucking blown to bits and shot at and they’ve worked in factories and mills and building sites and died young”.

How

International research across many countries has shown us how to involve; encourage; and learn from those many men who do not use violence or sexual violence. Based on the work of: Michael Flood in Australia, CRiVA in the UK, American Psychological Association (APA) in the US, the World Health Organisation RESPECT programme, systematic reviews of the evidence, the International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW) and organisations like White Ribbon and Promundo who promote healthy masculinity,

The most effective work:-

- Gives men and boys the permission to feel a range of emotions and be encouraged to label them and express them, ‘I am scared,’ ‘I am sad’.

- Encourages discussion around what gender is and how stereotypes impact on everyone.

- Looks at how not being able to express sadness or shame can turn into violence.

- Looks at the difference between physical and mental strength of character,

- Shows what the ‘man box’ of gender stereotyping is, how it limits men and how it is healthy to step outside its rules.

- Encourages critical conversations with other ‘real men’, talking about different ways of being and the acceptance of non-conformity.

- Celebrates masculine examples of empathy and caring as healthy and supports men to be fathers; including how to translate that into behaviours that avoid punitive, parental discipline.

- Provides the skills around how to challenge inequality as individuals and from within organisations.

- Looks at how to visibly model the changein a way that resists swopping one form of masculine dominance for another such as a ‘white knight saviour’ narrative.

- Finally, lets people know that sexual harassment, bullying and violence is about gender inequality, so making the connections through a gender transformative approach, making this about fairness and justice.

What happens when this message produces negative reactions? Tension and conflict are part of change and are to be expected and as far as possible, held and understood rather than avoided. How do you deal with resistance? By understanding it is a way of coping with threat. Who is threatened by what? Those advantaged by the current balance of power but also those who draw on extreme forms of masculinity to build a sense of self.

What does that look resistance look like? Research finds things like, #not all men, focusing on harm to the accused, suggesting accusations were false or driven by greed, prioritising harm or worrying about male privilege. Active undermining is one way to resist change.

Michael Flood’s work outlines the need for safe spaces, true participation, and skilled professionals using a variety of approaches, within a whole organisation approach, enduring long enough to hold the backlash. Also, securing powerful stakeholders and role models buy in, targeting those most likely to resist.

De-escalating resistance can often be achieved by simply not ‘blaming men’ but focusing on what they lose out on, what they can gain, and supporting them with examples in finding others ways to be a man.

Work at the University of the West of England has pioneered an approach to low level sexual violence through the Anti-Social Directed De-escalation, Reflection, Education, Support and Signposting programme (ADDRESS) in which early problematic behaviour is identified tackled, giving perpetrators the chance to change direction.

Anger and backlash can follow and may target women who represent the greatest ‘threat’ to male spaces and spheres of influence such as female politicians, women human rights defenders or women who report. Much of what is addressed here are individual or group approaches. There is therefore, also a wider ‘civil rights’ approach for criminal justice and policy work, protecting of women in public online and offline spaces. For example, the UK the Online Safety Bill will be attempting make a difference.

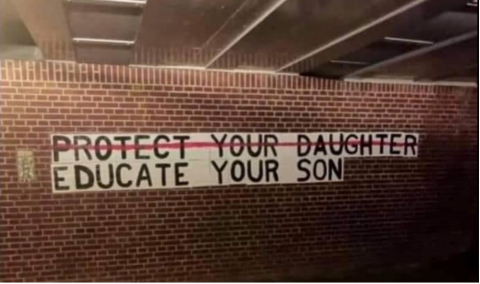

Let us leave behind the idea that men attack women and prevention is about telling women how to avoid it (Stanko, 1996). Social norms are the starting point for effective prevention and these can be taught.

Dr Jane Meyrick is a health psychologist and public health specialist working around sexual health and sexual violence prevention. She has recently published an ‘explainer’ what we know about sexual violence available through Routledge hyperlink with a 20% discount code FLA22.