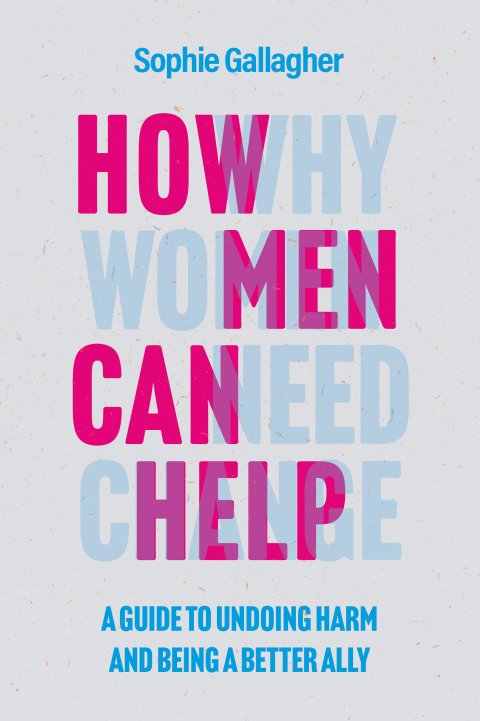

Why are women always tasked with ending men’s violence? Why are women both burdened with suffering under it and with solving it? Why do we never ask men to change their behaviour or to step up to counter misogyny and harm? How Men Can Help: A Guide To Undoing Harm and Being A Better Ally, by award-winning journalist and campaigner Sophie Gallagher provides the much-needed answers to these urgent questions. You can read an extract below.

***

It was a school night and we should have been in bed, and asleep, hours ago. On our way back from a gig, my friend and I had been dropped at the bus station in the middle of town and from there decided to walk the quickest route home – rather than the busiest or best-lit – to make up for the lost time. Two 17-year-old girls pacing alongside the suburban Essex bypass, a steady stream of cars driving by.

A lone man came into view on the path ahead. Standing in the centre of the pavement he was moving slowly towards us. Objectively, nothing had yet happened to indicate we should be scared – and of course we outnumbered him two to one – but my stomach lurched all the same. The only other routes available at this point were to turn back to where we’d come from, moving further away from the safety of our beds and still with no guarantee of security, to divert into a dark and totally empty park or to keep walking straight ahead. We quickened the pace, walking onwards, clasping our hands together.

No longer on the horizon, the man was now only a couple of feet away, eyes fixed on us. My mind raced through the numerous ways we could have avoided being in this situation: a different route, an earlier time, not going out at all. He said and did nothing as we passed – less than a metre apart – but as we glanced back, he was no longer walking in the opposite direction but had turned and was following us. Our unspoken fear felt realised: we ran.

This is not a remarkable story. It is painfully commonplace, taken from an encyclopaedic bank of stories that will ring familiar to women and girls, of all ages, across the UK. It ended when we, breathlessly, reached a nearby fish and chip shop that was mercifully open and occupied by a handful of people. Although there was no physical violence in this encounter, the underlying threat that we felt in those two minutes offers a snapshot into women’s everyday fear of men’s potential for violence. It shows the way that this fear can restrict our freedom to claim space in the world and the constant work to keep ourselves safe or the self-policing we undertake in a bid to mitigate the risk, despite knowing it is ultimately futile if a man really wishes to do us harm.

In the last few years, newspaper headlines, TV bulletins, radio broadcasts and conversations on social media have been dominated by high-profile examples of violence against women. Countless numbers of supposedly watershed moments and the media circus that ensues. The murders of Sabina Nessa, Ashling Murphy, Sarah Everard, Gabby Petito, Bibaa Henry, Nicole Smallman, Joy Morgan, Libby Squire, Grace Millane, and the many other women who got nowhere near the same level of column inches or attention. There has also been a widely documented rise in reports of drink spiking at nightclubs and the launch of campaigns like Soma Sara’s Everyone’s Invited, exposing rape culture in schools and higher education. The Covid-19 lockdown saw domestic abuse spiral to record highs with helplines like Refuge reporting a 60 per cent rise in the number of monthly contacts in what was described as a ‘shadow pandemic’. Women’s Aid reported that at one point in lockdown they had a queue of 21,000 users trying to access their live chat support. Even attempts by women to demonstrate solidarity and grief, like the Clapham Common vigil for Sarah Everard in March 2021, resulted in state violence.

Although these instances of violence are shocking – dashcam footage, court documents and CCTV stills of final bus journeys or supermarket trips, bringing the full horror of a woman’s last minutes into vivid and gruesome clarity – they are not surprising for women. Women are taught to live with a constant humming fear of men, an instinctive reflex, one that waxes and wanes on any given day, minute, moment. This does not mean they cower in sight of any and all men, but learn early that this is seen as a man’s world, we’re just living in it. To enter into public space is to do so at a potential cost to yourself, an eternal risk assessment.

Of course, women know that not all men present a danger, but we can also never be sure which ones do. In writing this book, I found it hard, almost impossible at times, to articulate the pervasiveness of this. For women, living with this knowledge is both excruciatingly conscious and at the same time so ingrained as to be invisible. It sits deep within me. It is self-preservation. It is the reason I have never walked alone through a park after dark, I sit near other women on the train if possible and I always know who is walking behind me. It is omnipresent.

Gender-based violence might be perceived as extreme – of course the consequences and harms are so – but seeing this violence only through a lens of extremity does a disservice to those it harms. It is not a lone force moving on the outskirts of society, it is the natural conclusion, a byproduct, of the patriarchal system and inequality we live under. The use of violence may feel disconnected from the everyday for many men, but it is made possible by a shared system that has preserved men’s dominance and women’s inferiority, held up by our history, our culture, our values, our media and our economic systems.

In a society that still has a gender pay gap, is content with women doing millions of hours of unpaid labour each year, does not have an equal representation of women in politics, on screen, or in boardrooms, laughs at rape jokes and only recently removed topless women from the pages of national newspapers, is it any wonder we’re still struggling with violence fuelled by male entitlement and power?